A decade after China founded the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), Washington’s early warnings — that it would become a diplomatic arm of Beijing and fall short of the standards upheld by U.S.-led institutions like the World Bank — have proven misplaced. Instead, the Beijing-based bank has emerged as a credible, collaborative, and climate-focused lender.

As the world contends with growing political divides and shifting climate priorities, new AIIB president Zou Jiayi faces the challenge of maintaining the institution’s integrity and focus. Under outgoing president Jin Liqun, the bank fulfilled his promise of being “lean, clean, and green.”

Since its launch in 2016 with a capital base of $100 billion, the AIIB has approved $67 billion in financing across 39 countries. Its 345 projects range from solar plants in Uzbekistan and rural roads in Ivory Coast to telecommunications satellites in Indonesia. Holding a triple-A credit rating, the bank directs about 67% of its lending toward climate adaptation and mitigation.

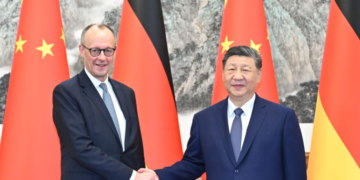

Though smaller than its global peers, the AIIB has ambitious plans — aiming to deploy another $75 billion by 2030. With 110 member countries, it stands as the world’s second-largest multilateral lender after the World Bank. Notably, many advanced economies such as the UK, Germany, France, and Australia joined despite U.S. objections. Only the United States and Japan chose to stay out.

What sets the AIIB apart is its transparency compared with China’s policy banks — the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China — which together have poured more than $470 billion into overseas financing under the Belt and Road Initiative, often criticized for fueling “debt trap” diplomacy. The AIIB, by contrast, complements rather than competes with the existing international financial order.

Roughly half of its projects are co-financed with institutions such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, partnerships that boost trust, speed up project approval, and share financing risks.The bank’s credibility has also been strengthened by its willingness to take positions that diverge from Beijing’s. It was quick to suspend operations in Russia following the invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and has defended the preferential creditor status of multilateral lenders during debt restructuring — a stance that contradicts China’s previous positions.

Perhaps most notably, the AIIB has built bridges where geopolitics often erect walls. Despite tense relations with China, India remains the AIIB’s second-largest shareholder and its biggest beneficiary. In 2024, South Asia accounted for 37% of the bank’s $1.57 billion in loan and guarantee revenues, financing projects like Chennai’s Metro Rail, the Orbital Rail Corridor in Haryana, and Enel Power’s vast solar project in Rajasthan’s Thar Desert.

For President Zou Jiayi, a former vice finance minister and seasoned multilateral negotiator known in China as the “tiger-fighting lady general,” the next phase will require balancing climate ambitions with growing energy demands. Her leadership will be tested as the global development agenda shifts.While the United States has not withdrawn from the World Bank or IMF, its policy direction is evolving. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has urged the World Bank to scale back its 45% climate financing target in favor of promoting broader energy security — potentially narrowing the space for collaboration with climate-oriented institutions like the AIIB.

Multilateral lenders are unlikely to finance coal projects, as Washington suggests, but the AIIB could explore nuclear energy as a sustainable alternative, particularly as artificial intelligence and industrial expansion drive massive increases in electricity demand.

The World Bank recently lifted its ban on financing nuclear power generation, opening the door for peers like the AIIB to follow — especially as new technologies reduce nuclear waste risks.Jin Liqun built a bank that defied expectations — efficient, green, and geopolitically balanced.

Zou Jiayi inherits an institution respected for working with, not against, the global financial system. Her task now is to safeguard that credibility amid rising tensions between climate imperatives and energy needs. If she succeeds, the AIIB could not only complement the World Bank but also help reshape the future of global development in an increasingly divided world.